The Harmonious Proportions of Christ

The tripartite division of the face was assumed by artists to represent ideal proportions, for example for the countenance of Jesus. But they also ‘constructed’ perfect facial features in other ways.

Martin Schongauer (c. 1445/1450–1491) and the Master E.S. (c. 1429–c. 1468) can serve as examples. In images of the sudarium, they made the heads of Christ – shown in a strict frontal orientation – symmetrical, as a reference to divine harmony. This was generated through equidistances (identical distances).

In Schongauer’s woodcut the widths of mouth, nose, and eyes of the Son of God correspond on the sudarium of St. Veronica. The width is the same as the distance between the inner corners of the eyes. The distances from the drawn central line to the two pupils are also measured the same way.

(Not contained in the construction drawing is the equilateral triangle as relation between eyes and nose or the height of the crown of the head, developed consistently from the measurements).

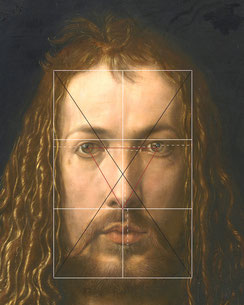

Dürer seems to have adapted the system of analogies and used it in a variety of ways. He used it, as shown, not only in the Head of a Man, but conspicuously also in his Christomorphic Munich Self-Portrait with Fur-Lined Robe (1500). The idea of the harmonious proportions of Christ is manifest in the construction.

Ultimately Dürer makes reference to the ancient connection between measure and measurement and God as mathematical ordering power from Old Testament Book of Wisdom 11:20. This religiously motivated guiding idea [1] connected with Vitruvius’s concept of measurement and apparently seamlessly with the anthropometric interests harboured by the artists of his time.

[1] Added to this was the conviction expressed during Dürer’s time that all measures could be found in the head of Christ, which could be identified with the geometric foundation of a beautiful image of Christ. In Stephan Fridolins devotional book Der Schatzbehalter oder Schrein der wahren Reichtümer des Heils und wahren Seligkeit (Nuremburg 1491) is written: “Das haubt, in dem die schetz aller formen und gestalten lagen, Das der spiegel aller Bildung und schonheit was.” (The head in which the treasure of all forms and shapes lies, This was the mirror of all attainment and beauty) (http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/is00306000); see Daniel HESS, ‘Dürers Selbstbildnis von 1500. “Alter Deus” oder “Neuer Apelles”?’, Mitteilungen des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg 77 (1990), 63–90, esp. 84–5.