Dürer's geometricized heads

Albrecht Dürer developed a hybrid concept for his head constructions. He adopted both the ‘recipes’ of the past as well as the praxis of the Italian Renaissance. He sought to produce ideal forms with harmonious proportions, or in the case of (self-) portraits, to improve upon the respective natural model in the work of art. For a long time he made use of, among other things, planimetric linear frames (of which there is no trace), basic geometric forms, and systems of analogies in order to determine the mass and forms of the head and the topography of the face. The measurement-aesthetic interventions lie below the threshold of visual perception.

In the Four Books of Human Proportion (1528) Dürer stated “Dann die menschlich gestalt kann nit mit richtscheyten oder zirckelen umbzogen werden ...”. (The human form cannot be circumscribed by straightedge or compass.) [1] But this ‘realisation’ was due to the necessity of offering apprentices reproducible schemata (which were indispensable for parallel projections). Yet it can be determined that Dürer designed the organic structures of many heads with these very drawing instruments: compass and ruler. Based on the density of construction steps, the Head of a Man turns out to be a laboratory of measurement aesthetics in the use of this method.

[1] "Denn die menschliche Gestalt kann nicht mit Richtscheiten und Zirkel umzogen werden ...". See the so-called aesthetic excursus in the fourth book of the teaching on proportion, in Albrecht DÜRER / Berthold HINZ, Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion (1528). Mit einem Katalog der Holzschnitte, ed. and trans. into modern German with commentary by Berthold Hinz (Berlin, 2011), 233 (T4v).

Constructed Form-Finding

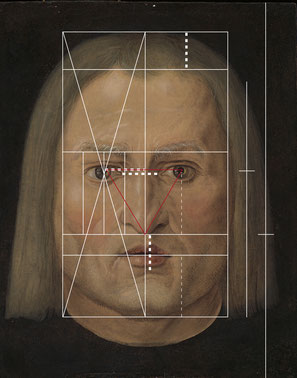

The foundation for schematising the head is a linear grid derived from the Vitruvian threefold division of the face (see The Rules of Vitruvius). It extends across the face as a vertical rectangle with six square fields. At the crown of the head a kind of painted notch can be seen and the centre of the nose is denoted with a stroke. Through these points runs the central vertical, with which the re-enactment of the construction begins.

As the unit for dividing the face into three equal segments, Dürer chose the distance between a line at the chin (the drawing of which can be seen through the painted layer) to the tip of the nose.

He projected this measure (one unit = the side of a square) upwards and to each side. In the Head of a Man he deviated from deploying the distance between the pupils as the unit for frontally shown heads, as is the case in his Self-Portrait with Fur-Trimmed Robe.

If diagonals are drawn through the framework, they run into the corners of the picture support. The format of the painting is thus also constitutive of the construction. This kind of layout recalls the heads overlaid with grids in the ‘sketchbooks’ of Villard de Honnecourt (see Villard de Honnecourt). (Among other reasons, the presumed early date of the painting is based on this similarity.)

As in Villard’s sketch, in the Head of a Man, diagonals run along the lower eyes. But Dürer only fit one of these in perfectly. He allowed the eye on the right to break out of the schema, probably to avoid an overly rigid facial expression. He proceeded in the same way with the Head of a Boy of 1508.

By means of a system of analogies, Dürer created various equal relationships in the Head of a Man: The left eye zone can be divided into equally wide strips, which run along the corners of the eye and cut through the pupil. Dürer originally wanted to incorporate the wings of the nose into this as well (as can be seen in the underdrawing) but these were ultimately widened.

A similar strip, turned on its side, also marks the distance between the end of the nose and the line of the opening of the mouth.

For the height of the crown, he used the distance between the inner corners of the eyes. This length can also be found from the central line to the left pupil. The height of the skullcap seems to have been chosen so that diagonals cut exactly through the eyes. This can be found frequently in Dürer’s head constructions.

What has not been drawn in is that the distances from the chin to the slit in the mouth and from the tip of the nose to the height of the pupils are the same. Dürer also developed the width of the face from a (curious) analogy.

The geometric structure also incorporates an equilateral, and thus ideal, triangle: It connects the pupils with the tip of the nose.

Dürer introduced the golden ratio no less than four times, in order to proportion his composition in accordance with the Renaissance formula for beauty. Only two are marked here: First, he divided the height of the panel vertically, with the line beneath the nose dividing the shorter length from the longer one. Second, at the height of the pupils, he divided the length of the face between the chin line below and the boundary of the hair above.

In addition to straight lines, Dürer also used circles and radii for describing corporeal forms. These are bound to the planimetric net.

A larger circle, which runs exactly around the corners, traces the neckline (underdrawn first then changed in the paint layer). Using the radius of the smaller one, which fits into the six fields lengthwise and borders on the edge of the shock of hair on both sides, the inner corners of the eyes and the corners of the mouth can be located.

How strokes of the compass preform specific ‘body components’ in Dürer’s work is illustrated by the London sheet with the body of a woman. The compass was deployed here several times, for example to establish the height of the waist beneath the chest rectangle. A circle drawn from the hollow of the throat even connects the lower contour of the breasts with the position of the eyes.